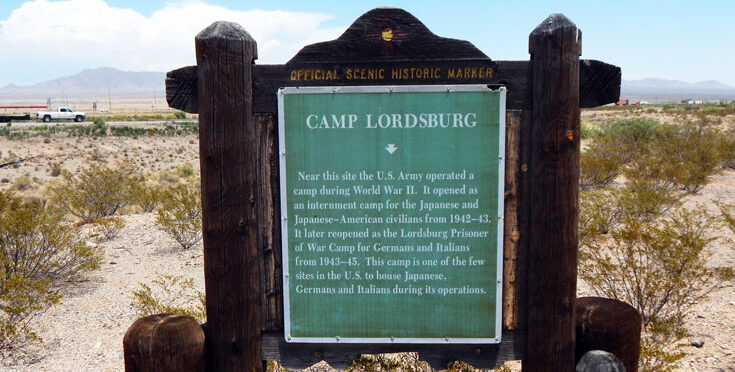

Photo By Mike Bibb: A New Mexico historical marker gives a brief history of the abandoned POW camp near Lordsburg, New Mexico.

Column By Mike Bibb

Not many folks are aware of the fact Safford had a Prisoner of War camp during World War II. A detachment of several hundred German and Italian men was present in the community from 1943-45.

The camp was located on south 8th Ave., in the general vicinity of today’s 24th St. There is no visual indication of its prior existence.

A satellite camp was also constructed near Angel Orchard, at the base of Mount Graham.

Like many of the camps, prisoners were used to perform various jobs around the area, including farm-related chores.

Seventy-five miles east in Lordsburg, New Mexico, a much larger facility was built. Unlike Safford’s camps, at various times Lordsburg housed all three Axis prisoners/internees – Germans, Italians, and Japanese.

Situated a few miles southeast of Lordsburg in the remote desert region of what is referred to as the “Bootheel” area of the state, a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers prison containment center was initially constructed to incarcerate Japanese resident enemy aliens – citizens of Japan who were living in America when war was declared shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii in early December 1941.

During the period, Lordsburg became a modern-day boom town. Construction of the POW camp required immense supplies of government-furnished concrete, timber, wood siding, electrical, plumbing, steel fencing and nearly everything else needed to build a project of considerable size.

Keep in mind, this was in early 1942. There was no four-lane interstate highway system to rush building materials and workers to a secluded sector. Rail service and a narrow two-lane road meandering from community to community provided the principal routes of transportation. A rural airport could handle small-sized aircraft.

Also, supplies were limited, as most of what was available were needed for the war effort.

Nevertheless, necessity and ingenuity helped make up for the deficits. The camp was made operational in less than a year.

In June 1942, the first Japanese prisoners arrived. Eventually, approximately 2,500 would be housed at the camp before being relocated to other camps to make room for the Italians.

From 1943 to 1944, an equal number of Italian POWs were interned at the Lordsburg facility. Local farms and ranches used many of them in their daily operations. Benefiting from the similarity of the Italian and Spanish languages, cooperation between local residents and Italian prisoners was enhanced. Generally, the Italians were not unruly and offered few security problems.

After the Italians moved out in April-May 1944, Lordsburg Camp was somewhat idle. Many Army personnel were transferred to other duties. However, the calm didn’t last long.

October and November 1944 witnessed 4,000 German prisoners arriving at the camp – designed to handle 3,000 inmates.

Another 1,500 were incarcerated shortly after that – primarily prisoners captured following D-Day and other European battles. At its zenith, Lordsburg would contain 5,500 German prisoners — almost double the camp’s capacity.

By this time in late 1944, Germany’s vaunted Third Reich was crumbling. The end would come a few months later – April 1945 – as Russia’s Red Army approached Berlin, Germany from the east, and the Allies closed in from the west.

A trapped Adolph Hitler, realizing the end was near, reportedly blew his brains out. His body was believed to have been burned inside his bunker.

Germany officially surrendered on May 8, 1945.

However, some people believe Hitler escaped by submarine to South America, as did other German war criminals.

With hostilities over in the European Theater, many American forces were transferred to the Pacific Theater to concentrate more intently on Japan.

Japan had determined to fight until its army and navy could fight no more. By March 1945, its forces had been pushed back to the southern island of Okinawa.

Seeing the island as a strategic point to launch a full-scale invasion on Japan’s mainland, the United States and its allies commenced the largest and most deadly battle of the war in the Pacific.

Lasting about five months, casualties were horrific on both sides. Over 12,000 American deaths were recorded, about 40% from Kamikaze suicide attacks on Navy ships.

Japan suffered an estimated 110,000 casualties of troops and civilians.

Still, Japan fought on – the Code of the Samurai was a difficult thing to extinguish.

Believing casualties would be even more extensive if an invasion of the mainland was to begin, American military and civilian officials decided to try a new weapon never used in war.

Coincidentally, the weapon was developed in another New Mexico location a few hundred miles north of Lordsburg. Los Alamos Laboratories was a super-secret government installation whose mission was to develop and fabricate nuclear energy into a device that could be dropped from an airplane and explode about 2,000 feet above the target.

On August 6 and 9, 1945 two atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, respectively, resulting in unimaginable death and destruction.

Japan remained silent. President Harry Truman warned Tokyo the U.S. had a third bomb it could deploy, if necessary.

Emperor Hirohito took the hint and announced Japan’s surrender on Aug. 15. Formal surrender ceremonies took place on Sept. 2, 1945, in Tokyo Harbor, aboard United States Battleship Missouri.

With the war over, there was no need to continue to maintain domestic POW camps. Most of the prisoners were released and sent home. The camps were eventually sold as government surplus.

The Lordsburg facility was opened for bid on May 1, 1947. Nearly all buildings, equipment, and operating systems – electrical, mechanical, water, sewage, etc. – were also auctioned.

Later, the War Assets Administration “transferred to the City of Lordsburg airport 358 acres of land and 14 buildings with installed equipment, walkways, and 2,000 feet of chain link fence.”

The Lordsburg Museum contains many of the prisoners’ artifacts and other items made by them while incarcerated.

The short four years in the 1940s was an unusual and historic period in the Bootheel community of Lordsburg. Local author and educator, Mollie Pressler, brought this information to the public’s attention in her 2022 book Camp Lordsburg. Many of the camp’s details in my article were gleaned from research and writings contained within her publication.

If interested, her book can be purchased by contacting www.CampLordsburg.com.