Photo by Nick Serpa/Cronkite News: Arizona Game & Fish uses trucks like this to haul water to catchments across the state, but some extremely remote catchments require water delivery via helicopter.

By Nick Serpa/Cronkite News

PHOENIX – The desert swelter weighs down on Jed Nitso as he approaches a small, man-made trough filled with green water that’s swarming with bees. A yardstick measurement confirms what he already knew: The water level is low.

With the twist of a lever, hundreds of gallons of water gush out of Nitso’s truck, flow down a 96-foot sheet of metal and fill a series of underground tanks. Twenty minutes later, the above-ground reservoir is full.

Nitso, a wildlife habitat heavy equipment operator for the Arizona Game & Fish Department, spent about half an hour checking on and refilling the catchment near Lake Pleasant. Some days, he helps repair roads or Game & Fish facilities. On others, he hauls equipment to project sites.

But when the state suffers from long stretches without rain, Nitso spends much of his time transporting truckloads of water to some of the most remote places in Arizona – the 3,000 Game & Fish-maintained water catchments that help keep Arizona’s wildlife alive.

The department has been building, expanding and maintaining these catchments since the 1940s, now spending thousands each year to ensure healthy wildlife populations – part of the department’s mission – even in the toughest conditions.

“It’s not an easy job,” Nitso said.

Catchments run dry

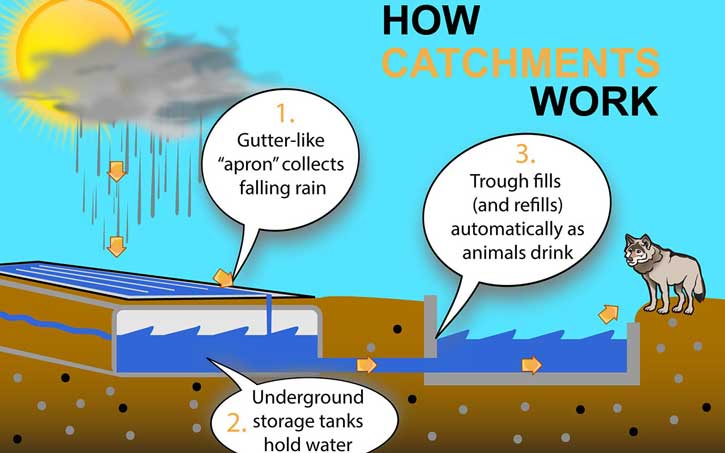

They go by several names: trick tanks, guzzlers, drinkers. The term Game & Fish officials use most frequently is catchment. Their purpose is simple – collect rainwater and deliver it to a trough so wild animals can drink.

People who spend a lot of time in Arizona’s wilderness may have stumbled across one. They typically consist of a few key elements: a trough to allow the animals to drink, a gutterlike ramp to collect rainwater and underground tanks to store the water. Some smaller catchments hold about 2,500 gallons of water. Others can hold nearly 10,000.

The catchments were designed to be self-sufficient, and they operate without any mechanical parts or electricity, using physics to ensure consistent water delivery. In theory, rain keeps the storage tanks full, so other than occasional maintenance, the catchments would rarely need to be touched by human hands.

But with Arizona in the grip of a decades-long drought, catchments run dry.

That means Nitso and other Game & Fish employees have to haul thousands of gallons of water into deserts, through forests, and up mountainsides. Game & Fish works with some nonprofits, such as the Arizona Elk Society, to maintain the catchments. The department only owns about a third of that number – various federal agencies, such as the Bureau of Land Management, own the rest.

Joseph Currie manages the catchments for the state, and he used to build and haul water to them for years before moving into the administrative side of wildlife management.

His budget for the current fiscal year is about $690,000, which he has to stretch to cover everything from the cost of the water to truck maintenance. Funding comes from a variety of sources, including grants, firearm-tax revenue and some proceeds from hunting permits.

Currie said it’s nearly impossible to predict how much water Game & Fish will need to haul each year, or how much it will cost.

“It all depends on the rains,” he said.

In the first six months this year, before monsoon storms swept the state, Arizona Game & Fish transported more than 650,000 gallons of water to catchments, he said. The cost ranges from hundreds to thousands per delivery, depending on the destination, amount and water source.

The Arizona Game & Fish Department accepts donations via text message to help fund the initiative. It also allows volunteers to “Adopt-a-Catchment,” helping to monitor water levels and complete light maintenance.

“It’s kind of funny,” Currie said. “We’re trying to get out of the water-hauling business by building these (catchments) bigger and more efficient, but with years like this, it’s inevitable. You’re going to be hauling a lot of water.”

Big job for employees

Maintaining the catchments is a challenging job that requires a certain kind of worker, Currie said. “There’s people that live for this,” he said. “There’s other people that have no clue that it even happens.”(sic)

Jed Nitso of Payson is the kind that lives for this kind of work.

Since he was a kid, Nitso said, he’d always wanted to work for a wildlife agency. He’s passionate about hunting, wildlife and spending time in nature, and he has worked with Game & Fish for more than 14 years.

Nitso travels across the state, from the Arizona Strip north of the Grand Canyon to the border with Mexico. Some catchments can be difficult to find because they don’t have coordinates listed or their locations were never properly recorded.

Wildlife management workers and rangers will stop by the catchments a few times a year and measure their water levels. Game & Fish also monitors rainfall to get a sense of which catchments might run dry.

Currie and Nitso recently hauled water to a catchment about 5 miles west of Lake Pleasant, off a network of bumpy dirt roads. But Currie emphasized that not all water deliveries are as easy to access as that one.

“This road might as well be on I-17, for me,” Currie said. “There are catchments that are on God-awful roads,” Currie said.

Some catchments can be accessed only by driving north into Utah and returning to Arizona, often a two-day journey. Many catchments aren’t near any sort of road.

Others are in locations so remote – such as bighorn sheep habitat – that water can only be delivered by helicopter. That’s done slowly, 150 gallons at a time, and it costs thousands of dollars an hour.

Despite the challenges, Nitso said he enjoys the job.

“On a weekly basis, I get to go into a lot of places where other people just go when they’re hunting,” Nitso said. “If I were to just say, ‘I’m going to go here on my own time,’ it might be one trip a year.”

When it’s hot, Game & Fish will often book Nitso a motel room or maybe he’ll sleep in an RV trailer or bunkhouse. But when the weather cools down, Nitso will set up a cot or tent and spend the night under the stars.

He said he looks forward to the inevitable encounters with wildlife, especially in northern Arizona.

“You never know when you’re going to come around the corner, and there’s going to be something standing in the road,” he said.

Human intervention

Arizona’s network of catchments has played a crucial role in maintaining healthy, stable populations of local wildlife for decades, Currie said.

Before large numbers of people had settled in Arizona, wildlife populations would fluctuate wildly with the rainfall, and in drier years, certain populations would experience huge die-offs. This realization was a big part of what led to the construction of catchments in the 1940s, Currie said.

The initial goal was to stabilize quail and dove populations, which were popular game at the time. The initial batch of concrete catchments was built primarily near Phoenix and was relatively small, only holding about 700 gallons of water.

But it didn’t take long, Currie said, for bigger species to discover the troves of water.

“They soon found after building a bunch of those that once the deer found them and the coyotes and everything else found them, they were drinking out of them, too.”

The small size of the first catchments, in addition to dry weather and frequent visits by larger animals, led to the need for water hauling. In the 1960s, workers built bigger catchments that could hold 6,000 gallons. Some of today’s catchments can hold close to 10,000 gallons and are built out of modern materials, such as fiberglass.

Catchments still are being built, but it’s not just to shore up water deficits because of dry weather: Some wildlife has been cut off from natural water sources by human incursion into their habitat.

This happened in the 1970s with the Central Arizona Project Canal, which planners knew would cut through wildlife habitats. The project’s budget included money for catchments adjacent to it.

The canal also poses a risk to animals that may fall in and get stuck, either by accident or when trying to access water, Currie said. That’s a big reason why Game & Fish maintains catchments on both sides of the waterway, which brings Colorado River water to Phoenix and Tucson.

Highways are another barrier for wildlife seeking food and water.

“When they straighten out a highway or widen it, it tends to become more of a barrier,” Currie said. “It’s like playing Frogger, if you’re the deer . . . You’ve got to try and keep from getting run over, so a lot of animals opt to not cross those roads.”

The catchments also reduce the chance of human encounters with wild animals. With a dependable water source, animals don’t need to venture into neighborhoods to survive.

“Sometimes when humans are blaming wildlife for ruining their flower pots or whatever, it’s because they moved into the animals’ backyard,” Currie said. “The animal is just trying to survive.”

There have been some unintended consequences of building the catchments; notably, attracting unexpected visitors.

The catchments were designed to be “wildlife exclusive,” Currie said, but they often attract domestic cattle and other large animals that ranchers let roam. These animals, particularly the cows, tend to camp out at catchments and quickly deplete the water, as well as risk damaging the structure.

To prevent this, Game & Fish often fences off catchments using steel fences designed to let in the animals the catchments are meant to attract – most wildlife can either pass through the fence or hop over it – while shutting out unwanted animals.

The department also strikes deals with ranchers to create secondary troughs that shoot off from the main catchment, so livestock can stay hydrated without affecting the water source for wild animals.

Even humans will use the catchments in dire circumstances because they are often the only reliable water source for miles.

Currie said illegal immigrants often use the catchments when crossing into Arizona from Mexico. “They have maps to our catchments leading all the way into town,” he said.

At times, he said, his crews have pulled up at catchments and found traces of recent human activity, including bags and plastic jugs.

“It’s saved people’s lives before,” Currie said. “It’s not the most fantastic water, but if it’s that or death, you might as well take the chance.”

Long-term impact

The catchments haven’t been entirely without controversy. Some researchers have questioned their impact on wildlife, arguing that a lack of quantifiable data makes measuring this difficult.

One 2007 report attempted to test whether draining water catchments would have an effect on bighorn sheep in the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Range, but researchers found “the removal of water sources” had no noticeable impact on mortality rates during their experiment.

The report notes that the scope of the study was limited, and there’s a need for additional research.

“Until long-term studies are completed … the question of whether or not (catchments) should be constructed or maintained will continue to be controversial and largely a political matter,” the report said.

Despite the questions, Nitso said he’s witnessed the catchments’ impact firsthand on multiple occasions.

Several weeks ago, he was hauling water to a catchment near Quartzsite and encountered wild sheep drinking from it. By the time he got there, the catchment was almost dry. Nitso said he hauled nearly 5,000 gallons of water to the catchment that day.

“I felt pretty good knowing that those sheep will have plenty of water to drink for the next several weeks,” he said.

Another time, Nitso said he encountered nearly 100 elk drinking from a catchment near Tusayan. Rainwater couldn’t keep that catchment full, so Game & Fish connected it to a nearby wastewater treatment plant.

Ultimately, Currie said he thinks the catchments have had an impact.

“The whole world can come here and enjoy desert wildlife because we do this,” Currie said. “To me, that’s really meaningful.”