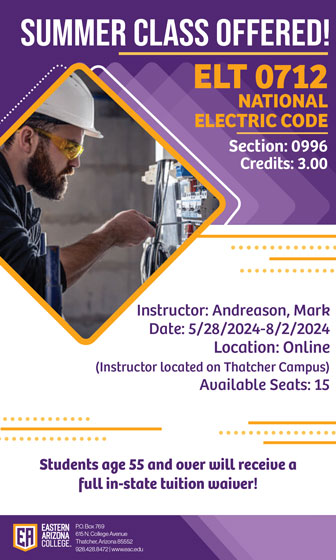

Photo Courtesy National Park Service: Workers assess the Wahweap boat launch ramp at Lake Powell in July 2021 when falling low lake levels pulled the water’s edge back from the end of the ramp. State and federal officials are scrambling to come up with plans to protect the river and its reservoirs, griped in a historic drought.

By Alexis Waiss/Cronkite News

WASHINGTON – Federal officials said they will consider a plan by Arizona and five other Colorado River basin states on how to further cut water consumption, even though the biggest user in the basin – California – has not signed off on it.

California released its own plan late Tuesday in response to the six-state proposal that it said unfairly forced California to shoulder many of the cuts by counting water losses through evaporation and transmission, which it said, “directly conflicts with … existing law.”

The six-state proposal came Monday just one day before a Bureau of Reclamation deadline for states to come up with their own plan or risk having one imposed on them. Experts said California was part of those negotiations, but “simply did not agree with the way the model was developed.”

The states’ proposal does not allocate specific cuts to specific states or users, but it is an acknowledgment by the six states – Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming – that the current drought-related reductions in usage that were spelled out in a 2007 agreement are simply insufficient in the current climate crisis.

“We recognize that over the past twenty-plus years there is simply far less water flowing into the Colorado River system than the amount that leaves it and that we have effectively run out of storage to deplete,” said the agreement, which the states called a Consensus-Based Modeling Alternative.

The plan aims to protect water levels in Lake Powell by raising the level at which current water reduction plans would be triggered.

It would also raise threshold levels in Lake Mead, and calls for an additional 1.543 million acre-feet in “evaporation and system losses” to be absorbed by the state when the lake falls below 1,145 feet. The lake was at 1,046 this week, according to Bureau of Reclamation data.

In its plan, California said the proposed new method of apportioning cuts based on system and evaporation losses “would direct the majority of water use reductions needed in the Lower Basin to California water users,” contrary to current law regarding river usage.

The six-state plan also proposes reductions of 250,000 acre-feet when Lake Mead falls below 1,030 feet and 200,000 acre-feet when it falls below 1,020 feet. In each of those cases, California would bear 59% of the reductions, Arizona 37%, and Nevada the remaining 4%.

The plans are meant to guide the Bureau of Reclamation as it prepares an environmental impact statement, set for release this spring, on the impact of any changes to regulations governing the management of river water and the dams on the Colorado River. Those changes could be laid out this fall, said an Interior Department spokesperson in an emailed statement Tuesday.

“This collaborative supplemental process is our strongest immediate tool to help improve and protect the short-term sustainability of the Colorado River System by empowering the Bureau of Reclamation with additional alternatives and tools needed to address the likelihood of continued low-runoff conditions across the Basin over the next two years,” the statement said.

It comes as the Southwest is locked in a historic two-decade drought that has dropped the level of the Colorado River and its reservoirs to dangerously low levels. More than 40 million people rely on water from the river, which powers hydroelectric plants that generate power for customers in seven states and parts of Mexico.

While the plan from the state can give the federal government a roadmap on how to allocate future water cuts, experts said there is still much work to be done on what one called “a very complicated situation.”

“The hard part is still ahead,” said Sarah Porter, the director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University. “The likelihood of agreement on cuts to water users that water users will agree to cut is still low.”

Tyler Cherry, the Interior spokesperson, said negotiations going forward will include not just state and federal officials, but other stakeholders including tribes, farmers, water managers, irrigators, and more, to create a plan that has as much support and consensus as possible.

Requests for comment from California’s Colorado River Board were not immediately returned Tuesday. But Phoenix Water Resource Management Advisor Cynthia Campbell said one of the challenges states will need to overcome is California’s difference of opinion on water reduction strategy.

“My understanding is that California was always in the negotiations. They were at the table so they weren’t excluded,” Campbell said. “They simply did not agree with the way the model was developed. I’m not sure that they liked the idea of evaporative losses.”

In a news release announcing Monday’s agreement, Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke called the model “a key step in the ongoing dialogue among the seven Basin states.” Brenda Burman, general manager of the Central Arizona Project, which carries water from the Colorado River to Phoenix and Tucson, said in the same release that the plan is a critical step to “lay the groundwork for finding durable long-term solutions” to the region’s water crisis.

One thing that the plan does not touch on, Campbell said, is how climate change, in tandem with cyclical drought and water over-usage could negatively affect water levels. She thinks that’s an oversight.

“We think that that should be considered to some extent because you could have a situation that was never intended,” Campbell said of the impact of climate change. “People could be cut off permanently on the fact that the river just won’t yield the amount that has been allocated.”

The agreement is careful to caution that “negotiations to implement actions contemplated by this CBMA … have not yet been completed, and in many cases have not yet begun” between the states and other stakeholders. Porter agreed there is still much planning and negotiating to be done.

“There is no agreement on how additional cuts would be felt, distributed there. And that’s the hardest part,” Porter said. “So in the state of Arizona, we would need … to have the legislature approve and the governor sign changes to the Colorado Compact.”