File Photo By Vandana Ravikumar/Cronkite News: The Supreme Court ruled Tuesday that tribal police can detain non-tribal members in certain circumstances, despite a general prohibition on tribal authorities imposing their law on others, because to do otherwise would make it hard for tribes to protect themselves from ongoing threats.

By Brooke Newman/Cronkite News

WASHINGTON D.C. – Tribal police have the authority to detain non-Natives traveling through reservation land if the officer has a reasonable belief that the suspect violated state or federal law, the Supreme Court ruled Tuesday.

The unanimous ruling overturned lower courts that said a Crow police officer should not have held a nontribal member who was found to have drugs and weapons in his truck. The Supreme Court said that the lower courts’ rulings would “make it difficult for tribes to protect themselves against ongoing threats.”

Calls seeking comment Tuesday from Arizona tribes and tribal police agencies were not immediately returned. But advocates welcomed the ruling that one said addresses “a crucial issue of law enforcement and safety in Indian Country.”

“The Supreme Court got it right, and upheld tribal authority to do the bare minimum of what any police force should be able to do to protect their homeland and the public safety of members of the community,” said Heather Whiteman Runs Him, director of the Tribal Justice Center at the University of Arizona.

The case began early on the morning of Feb. 26, 2016, when Crow Police Department Officer James Saylor noticed a truck stopped on the side of U.S. Route 212 on reservation land in southern Montana. Saylor stopped, thinking the driver might need assistance.

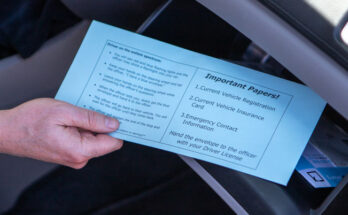

As Saylor approached the driver’s side of the truck, driver Joshua Cooley rolled down, then rolled back up, his window. When he rolled it down again at Saylor’s request, the officer noticed that Cooley, who “appeared to be non-native,” had “watery, bloodshot eyes.”

After he noticed two semi-automatic rifles on the front seat, Saylor asked Cooley to get out of the truck for a pat-down search and called for assistance from tribal and county officers. While waiting for them to arrive, Saylor returned to turn off the still-running truck and spotted a glass pipe and a bag containing methamphetamine, according to court documents.

When the other officers arrived, including a federal Bureau of Indian Affairs officer, they told Saylor to “seize any contraband in plain view,” which led to the discovery of more methamphetamine.

Cooley was indicted in federal district court on drug and gun charges but moved to have the drug evidence suppressed. He argued that Saylor did not have the authority as a tribal police officer to investigate “nonapparent violations of state or federal law by a non-Indian on a public right-of-way crossing the reservation.”

The district court agreed, and a panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld that ruling in March 2019, noting that Saylor made no attempt to determine whether Cooley was a tribal member or not.

The full 9th Circuit refused to reconsider the ruling, which one dissenting judge said would “blow … a gaping hole in tribal law enforcement.”

But the Supreme Court said Tuesday that while its previous rulings support “the general proposition that the inherent sovereign powers of an Indian tribe do not extend to the activities of nonmembers of the tribe … it is not an absolute rule.”

Justice Stephen Breyer, who wrote the opinion for the unanimous court, noted that there are two exceptions to that rule, one of which “fit like a glove” in this case. Those are actions to protect the health or welfare of the tribe.

“To deny a tribal police officer authority to search and detain for a reasonable time any person he or she believes may commit or has committed a crime would make it difficult for tribes to protect themselves against ongoing threats,” Breyer wrote. “Such threats may be posed by, for instance, non-Indian drunk drivers, transporters of contraband, or other criminal offenders operating on roads within the boundaries of a tribal reservation.”

Robert Miller, a professor at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, said the high court’s ruling is “important and welcomed.” He said it is the first time the court has interpreted the health and welfare exception to its limits on tribal sovereignty.

“This decision will be very popular among people who support Indian sovereignty,” Miller said. “Millions of non-Indians live on reservation land, so this is a crucial issue of law enforcement and safety in Indian Country.”

Whiteman Runs Him, a member of the Crow tribe, said there are typically only two to four officers to patrol the 2.5 million-acre reservation, which has been hit hard by the methamphetamine epidemic. The court “applied common sense” in its ruling, which will put more tools in the hands of tribal police officers to fight drug and human trafficking, she said.

“The ability of law enforcement to respond to crises is really a matter of life and death to many tribal citizens and many non-Indian citizens living on or traveling through the reservation,” Whiteman Runs Him said.