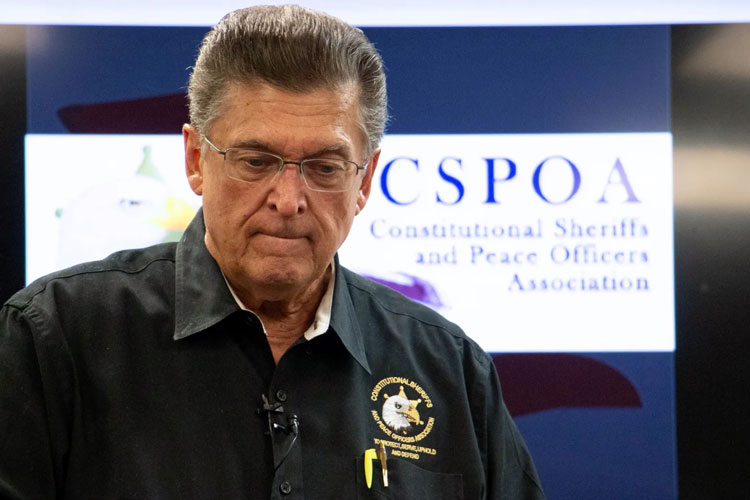

Photo by Isaac Stone Simonelli/AZCIR: Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association founder Richard Mack speaks to a crowd of about 100 people at a Yavapai County Preparedness Team meeting in Chino Valley, Ariz., on Oct. 8, 2022.

By TJ L’Heureux, Adrienne Washington, Albert Serna Jr., Anisa Shabir and Isaac Stone Simonelli

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. — Against the background hum of the convention center, Dar Leaf settled into a club chair to explain the sacred mission of America’s sheriffs, his bright blue eyes and warm smile belying the intensity of the cause.

“The sheriff is supposed to be protecting the public from evil,” the chief law enforcement officer for Barry County, Michigan, said during a break in the National Sheriffs’ Association 2023 conference. “When your government is evil or out of line, that’s what the sheriff is there for, protecting them from that.”

Leaf is on the advisory board of the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, founded in 2011 by former Arizona sheriff Richard Mack. The group, known as CSPOA, teaches that elected sheriffs must “protect their citizens from the overreach of an out-of-control federal government” by refusing to enforce any law they deem unconstitutional or “unjust.”

“The safest way to achieve that is to have local law enforcement understand that they have no obligation to enforce such laws,” Mack said in an interview. “They’re not laws at all anyway. If they’re unjust laws, they are laws of tyranny.”

The sheriffs’ group has railed against gun control laws, COVID-19 mask mandates, and public health restrictions, as well as alleged election fraud. It has also quietly spread its ideology across the country, seeking to become more mainstream in part by securing state approval for taxpayer-funded law enforcement training, the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism found.

Over the last five years, the group has hosted training, rallies, speeches, and meetings in at least 30 states for law enforcement officers, political figures, private organizations, and members of the public, according to the Howard Center’s seven-month probe, conducted in collaboration with the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting.

The group has held formal training on its “constitutional” curriculum for law enforcement officers in at least 13 of those states. In six states, the training was approved for officers’ continuing education credits. The group also has supporters who sit on three state boards in charge of law enforcement training standards.

Legal experts warn that such training – especially when it’s approved for state credit – can undermine the democratic processes enshrined in the U.S. Constitution and is part of a “broader insurrectionist ideology” that has gripped the nation since the 2020 presidential election.

“They have no authority, not under their state constitutions or implementing statutes to decide what’s constitutional and what’s not constitutional. That’s what courts have the authority to do, not sheriffs,” said Mary McCord, a former federal prosecutor and executive director of the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection at Georgetown University.

“There’s another sort of evil lurking there,” McCord added, “because CSPOA is now essentially part of a broader movement in the United States to think it’s OK to use political violence if we disagree with some sort of government policy.”

At least one state, Texas, canceled credit for the sheriffs’ training after determining the course content – which it said included a reference to “this is a war” – was more political than educational. But other states, such as Tennessee, have approved the training, in part because it was hosted by a local law enforcement agency.

Unlike other law enforcement continuing education, such as firearms training, the sheriffs’ curriculum is largely a polemic on the alleged constitutional underpinnings of sheriffs’ absolute authority to both interpret and refuse to enforce certain laws. One brochure advertising the group’s seminars states: “The County Sheriff is the one who can say to the feds, ‘Beyond these bounds, you shall not pass.’”

Since 2018, the Howard Center-AZCIR investigation found, at least 69 sheriffs nationwide have either been identified as members of the group or publicly supported it, though at least one later disavowed the organization. A 2021 survey of sheriffs by academic researchers working with the nonprofit Marshall Project found that more than 200 of the estimated 500 sheriffs who responded agreed with the group’s ideology.

Amy Cooter, research director at the Middlebury Institute Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism, said many sheriffs join the group from “a misinformed but well-meaning perspective.” But, she added, it also allows some sheriffs to “potentially engage in extremism by not enforcing legal, lawful, legitimate orders.”

Nationwide, there are some 3,000 sheriffs, whose salaries are funded by taxpayers. They serve as the chief law enforcement officers in their counties and are the only elected peace officers in the country. They appoint deputy sheriffs and jailers and service the courts in their jurisdictions. Sheriffs hold immense sway over what happens in their counties, especially rural ones.

Some states have pushed back against the group’s training efforts, and not all sheriffs subscribe to the group’s ideology. Many at the National Sheriffs’ Association conference distanced themselves from the constitutional sheriffs or claimed not to know what they were about.

“When I took an oath 17 years ago as sheriff, I took the oath to uphold the Constitution, not overstep it,” said Troy Wellman, sheriff of Moody County, South Dakota, and a vice president of the National Sheriffs’ Association.

And there has been public pushback in some counties led by “constitutional sheriffs.” In Klickitat County, Washington, residents alleged Sheriff Bob Songer, a board member of the sheriffs’ group, engaged in fearmongering and intimidation. He was the target of a formal complaint in 2022 that the state’s law enforcement standards agency ultimately dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.

The public-facing image of the sheriffs’ group, which is led by white men, prominently features the American flag and the experiences of Black civil rights icons who pushed back against unjust laws. But details of its operations are closely held, and its finances are shielded from public scrutiny. It was briefly registered as a nonprofit in Arizona, but internal records indicate it is now a private company.

The group does not release its list of dues-paying members, nor does it publicize information about where or how it conducts training. The sympathies of the group’s leaders for right-wing, white-nationalist extremist causes, however, are well documented.

Mack was an early board member of the Oath Keepers, the group involved in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. Although he said he split with the group several years ago when it became a militia, Mack still speaks at Oath Keeper-affiliated rallies.

Leaf was investigated, but not charged, in connection with the Michigan attorney general’s investigation into the alleged illegal seizure and breach of vote-counting machines in 2020. He also appeared at an election-denier rally with two men later charged in the conspiracy to kidnap Michigan’s Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer.

Michael Peroutka, another sheriffs group board member and former candidate for Maryland’s attorney general, was once affiliated with the League of the South, which supports “a free and independent Southern republic.” At a 2019 sheriffs’ training event, he said, “There is a creator God. Our rights come from him. The purpose of civil government is to secure and defend God-given rights.”

Jon Lewis, a research fellow at George Washington University’s Program on Extremism, described the sheriffs’ group as “insidious” and said it had become “mainstream standard-bearers for entrance into more violent forms of extremism.”

“Just because it’s not as overt in their subversion of the democratic system, just because it’s quieter about how it does it and what it’s calling for, doesn’t make the ideas any less dangerous,” said Lewis.

National Expansion

Two heart attacks. Plans for a book about sheriffs and the pandemic. And a new board position at the right-wing political organization America’s Frontline Doctors. These were the reasons Mack cited in November 2022 for stepping down as head of daily operations for the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, records show.

Mack tapped far-right radio personality Sam Bushman to replace him as chief executive officer, though Mack remains board chairman and retains all authority.

Bushman runs Liberty News Radio, which syndicates white-supremacist programs across the country, including the pro-Confederate show Political Cesspool, which hosted former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard David Duke as recently as May 20, 2023. He declined to answer reporters’ written questions.

“What we really need to do is scale up our training. That’s who we are, that’s what we do. And the need for it has never been greater,” Bushman said during a January 2023 board meeting.

Most law enforcement officers are required to participate in taxpayer-funded, continuing education to stay current on their certifications. Training typically focuses on keeping officers sharp in several skill sets, including using firearms and encountering mental health situations.

To track the spread of the sheriffs’ group, the Howard Center filed public records requests with state law enforcement standards boards in 48 states and several sheriffs’ offices, related to the group’s training and communications with officials from 2018 to 2023. The latest records received were from early June 2023.

In that time, the sheriffs’ group conducted training in at least 13 states. In at least five of those states, the training received continuing education credit, and in six of them, the states’ training regulation board approved the sheriffs’ curriculum. An internal November 2022 email shows the sheriffs’ group claimed its training had been approved for accreditation in seven states.

Reporters also found that members and affiliates of the sheriffs’ group sit on the law enforcement regulatory boards in Arizona, Florida, and Maine. These state training boards determine what officers are taught and which law enforcement philosophies to adopt. In Florida, board approval is required for training to receive continuing education credit.

Lessons must be certified by a state’s training board for officers to receive credit in at least 30 states, reporters found, but approval is not necessary for official credit in at least 16 states. The laws about oversight of law enforcement training vary across states, according to a review of the law enforcement standards and training oversight agencies in each state and the District of Columbia.

Mack claimed in a November 2022 conference call that his organization had trained close to 1,000 sheriffs nationwide, in addition to an unspecified number of deputies, undersheriffs, and police chiefs.

Experts caution such figures can be inflated. But, as Mack noted, it is nearly impossible to know how many deputies have learned about the organization’s philosophy through someone who attended the training.

Leaf, the 58-year-old Michigan sheriff, said he brings back to his command what he learns during the sheriffs’ training because “it’s very important I have my sergeants on board with my philosophies.”

The recordings of the sheriffs’ advisory board meetings make clear that a new strategy has emerged focused on holding training near where board members are based, thus minimizing the travel needed to conduct them. Bushman said they would like to see active members, including board members and sheriffs, conduct those trainings in their locales.

Gaining state-sponsored accreditation also remains a focus of the group, board discussions show.

“We can scale up more of these events to get out more training faster. It takes certifications in the states to do that,” Bushman said in a January meeting.

The group’s then-national director of administration, Tonya Benson, said in a November 2022 email to board members and supporters that “the more states we can get approval and accreditation for the curriculum, the better.” She added: “The best way to get approval is for a ‘friendly’ sheriff to submit the request.”

Experts say the formal training gives the sheriffs’ ideas a facade of authority, as well as provides an opportunity to reach a greater target audience: law enforcement officials.

“If I’m a young police officer, and I have somebody standing in front of me, you know, in a law enforcement uniform, telling me the law, that I’m allowed to interpret the law the way I choose or the way he suggests, how am I supposed to believe that that’s improper if that person is duly certified under the state authority?” asked Michael German, a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty & National Security Program, who spent 16 years as an FBI agent.

“It validates their false information in a way that will make it harder for rank-and-file officers to resist it,” German said, adding that when law enforcement officers are “allowed to interpret the law as they see fit, the chances for error and abuse go way up.”

Partial Pushback

Despite its spread, the group has faced pushback in some states, including in Texas, where it claimed in December 2021 to have trained about one-fifth of the state’s 254 sheriffs.

After news reports revealed the extent of the group’s involvement with Texas sheriffs, the state agency that regulates law enforcement training investigated and then banned future constitutional sheriffs’ training for credit.

The group’s training was “best categorized as political discourse,” the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement wrote in a May 26, 2023, letter to Mack.

In Illinois, where roughly 90% of the state’s sheriffs vowed not to enforce the state’s new ban on semiautomatic weapons, a state official declined to give officers credit for the constitutional sheriffs’ training, saying the material wasn’t filed early enough and the state already taught constitutional concepts.

Nebraska’s Police Standards Advisory Council told reporters it would not certify the sheriffs’ group’s training because it considered the group to be a political organization and the agency avoids any such affiliation.

Even so, training doesn’t need approval in Nebraska, and the state’s sheriffs may independently partner with the constitutional sheriffs’ group.

That’s what happened in Tennessee. That state’s law enforcement standards board must approve training for credit, but officials also said they approve training hosted by local sheriff’s offices, regardless of content.

“We just have to find the right sheriff or right person who can… kind of push that through,” Benson, the group’s national director of administration, said in a January board meeting recording. “It’s kind of a simple process. It just takes someone to kind of babysit it, hound dog it, and be on top of it to get the approval.”

Lt. Joseph Gill, director of training for Madison County Sheriff’s Office in Tennessee, became the right person. A July 11, 2023, training was approved by Tennessee’s law enforcement commission, as required for accreditation. “It wasn’t really a training, I mean, he (Richard Mack) just came and spoke,” said Max Milam, a training specialist in the sheriff’s office.

The Tennessee approval came even though the sheriffs’ group had declined to provide its presentation materials. Instead, it provided an outline comparing its philosophy with that of civil rights leaders such as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks.

“Civil disobedience has an honorable tradition in the United States,” German noted. “But the government’s not allowed to engage in civil disobedience. And, as government officials, they have a duty to comply with the law.”

Washington state has been the scene of the most organized pushback against the sheriffs’ group, reporters found.

During their 2021-2022 legislative session, lawmakers empowered Washington’s police oversight agency to hold law enforcement officers accountable for their affiliations with extremist groups. The agency must now expand required background checks to include any extremist affiliations and revoke an officer’s license for misconduct.

“I don’t think it’s a big stretch to say that when we’ve got folks now literally with the power to kill someone that we should expect them to adhere to very high standards of behavior, of impartiality,” said Jamie Pedersen, a state senator from Seattle who sponsored the new law.

Internal working group emails revealed the challenges in developing a workable definition of domestic “extremism.” Regulators agreed such groups seek “to undermine the democratic process” through violence or intimidation or promote the idea that their interpretation of the law “supersedes those of any other federal, state, or local authority.”

“One of our issues was, beyond the Patriot Front and Proud Boys and Klan members and all of that, was the CSPOA,” Olympia attorney Leslie Cushman said, referring to the sheriffs’ group. Cushman helped advise legislators on behalf of the Washington Coalition for Police Accountability, a group of advocates and people who have lost loved ones to police violence.

“Of grave concern is the relationship of the CSPOA to the Oathkeepers,” Cushman wrote in a March 3, 2022, email to the working group.

The sheriffs’ group had made inroads in Washington state in early 2021 when it hosted two events there.

In February 2022, the state’s law enforcement training commission received a complaint from a group of unnamed residents about Songer, the Klickitat County sheriff since 2014. It alleged instances in which Songer amplified “baseless rumors” about anti-racism activists and used a local radio show to name people critical of his policies.

Songer also created a “posse” of nearly 150 citizen volunteers, and he told the federal government in 2021 to “stay out of our county” after the Justice Department called on the FBI to work with federal prosecutors on threats of violence against school officials.

The complaint cited Songer’s alleged support for extremist organizations, such as Patriot Prayer, which rallies with members of Proud Boys; and the People’s Rights Network, founded by Ammon Bundy, who led a 40-day-long standoff with federal authorities in 2016.

Songer confirmed he attended meetings for People’s Rights Network and Patriot Prayer, but said he didn’t know Patriot Prayer had ties to Proud Boys.

“Having an extreme-right organization dictate to our local county official, it puts a stamp of approval on, you know, discrimination and racism,” said Lynn Mason, a Klickitat County resident who campaigned against Songer during his 2022 reelection bid.

The Washington Commission later determined that “the issues raised (in the complaint) were not within” its jurisdiction and said, “no further action will be taken.”

The state’s new extremism law applies to “certified” law enforcement officers. County sheriffs are elected officials and not all have gone through the law enforcement certification process. Members of Songer’s posse are also excluded from the law because they don’t have to be certified.

“They can be an enormous vigilante group,” Cushman said. “I know people in Klickitat County, Skamania, and Clark County are intimidated and afraid to speak up.”

Looking Forward

Bushman has said that one of his key aims as the group’s new operational leader is to increase the number of state directors who report to him.

But in recent months, there’s been an exodus of the group’s leaders and top supporters. Half of the eight-member advisory board has resigned, and one of the group’s state directors complained the organization “is struggling to remain relevant.”

Internal records indicate that the dispute with America’s Frontline Doctors may have played a role.

In November, the founder of the doctors’ group – a convicted Jan. 6 protester – named Mack along with other board members in a lawsuit that alleged “financial improprieties.” In April, the doctors’ group issued a press release saying it had removed Mack from the board and reported him to local police for allegedly embezzling $350,000 from the organization’s bank account. Police closed the case four weeks later, saying the organization did not provide sufficient documentation to prove a crime had been committed.

The 70-year-old former sheriff said in an interview that he simply moved funds to another of the doctors’ group’s accounts to protect the organization’s finances. He claimed to have been dropped as a named defendant in the lawsuit, but the most recent court filings in the case don’t support that.

Mack also indicated that some of the sheriffs on his board were unhappy with him and Bushman, but did not further elaborate.

“The CSPOA, since COVID hit, has grown exponentially,” Bushman said during the November 2022 board meeting in which he was named to succeed Mack. “This is an attempt to carry forward Richard Mack’s legacy. This is a growth effort.”

A review of internal meetings and Mack’s weekly webinars show there were at least six state directors in Texas, Virginia, Utah, Arizona, and California, though at least one has left the group since June 2023.

Bushman said he had a plan to increase that figure to between 30 and 40 by the end of 2023. According to recordings of the group’s meetings, increasing the number of state directors could help the organization solicit formal credit for its training in more states.

The group’s California state director, Jack Frost, also suggested during the November meeting that the group focus on creating a template for conducting voter fraud investigations because “I don’t think our sheriffs and our investigators have a clue what they need to do.”

Internal meeting agendas and recordings, obtained under Public Information Act requests, showed that the sheriffs’ group planned to partner ahead of the 2024 elections with True the Vote, a right-wing Texas nonprofit that challenged the legitimacy of the last presidential election.

A February 2023 meeting agenda said the two organizations were working to create a “template for comprehensive and effective voter and election integrity” investigations. Discussion of collaboration was listed on the board’s April 2023 meeting agenda. But by May, when the group held four meetings, there was no discussion of elections.

“We would love to continue to work with them on mutual concerns, but it appears that they’re too busy,” Mack told reporters.

While sheriffs offices’ are sometimes asked to assist election officials in investigating allegations of election fraud, a growing number of sheriffs have claimed broad authority to launch voter fraud investigations.

McCord, the Georgetown law professor, likened such sheriffs’ actions to “vigilantism.”

“This is almost like a sheriff being willing to engage in vigilantism, which sends a broader message that vigilantism is actually acceptable. And vigilantism, when it is against the government, is insurrection,” McCord said.

The group’s effort to train more law enforcement officers also increases the number of them who buy into its constitutional philosophy, creating “conditions for some kind of potential brinkmanship or conflict” between local and state or federal law enforcement, said Lewis, the George Washington University research fellow.

“This is kind of the tipping point,” Lewis said. “Hundreds of sheriffs across the country have gained the trust of their locales and are now sitting in elected office … their training booklets from CSPOA right next to them. And I think that’s always going to be a pretty significant cause for concern.”

Brendon Derr of the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting and Jimmy Cloutier, Heaven LaMartz, and Annabella Medina of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism contributed to this story.

This project, In the Sheriff We Trust, was produced by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism, in collaboration with the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting. The Howard Center is based at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication and is an initiative of the Scripps Howard Fund in honor of the late news industry executive and pioneer Roy W. Howard. AZCIR is a nonpartisan, nonprofit newsroom that focuses on data-driven investigative journalism.