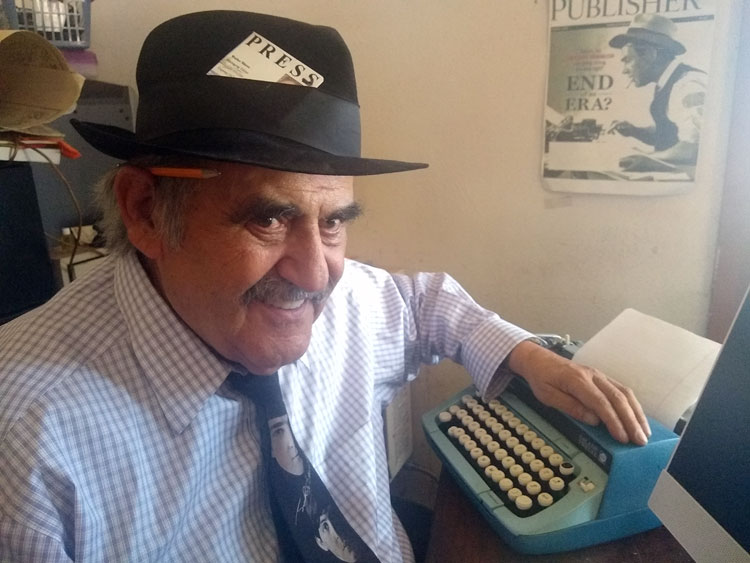

Walt Mares Photo/Gila Herald

Considered themselves ‘just regular guys’

Column By Walt Mares

It happened more than 14 years ago. It was a unique funeral ceremony at the Franklin Cemetery near Duncan on Feb. 15, 2007. There were no long-winded speeches and very few flowers. It was a cool morning. At times there was a brisk breeze. Most people wore sweaters or jackets.

The homemade pine casket of the man to be buried was hauled there from Safford in the back of a white pickup truck. The escort was made up of several men on motorcycles wearing their leathers. It was their way of paying tribute to the friend to whom they would be bidding farewell. After all, he, too, was a biker through and through.

What was most noticeable, besides the impressive array of motorcycles, the men in their leathers, and the thundering sound of the bikes, was that the word “hero” was not uttered once at former Marine and Vietnam combat veteran Michael David Cranford’s funeral at Franklin. About 300 people attended, far more than expected for the simple ceremony that had not been publicized.

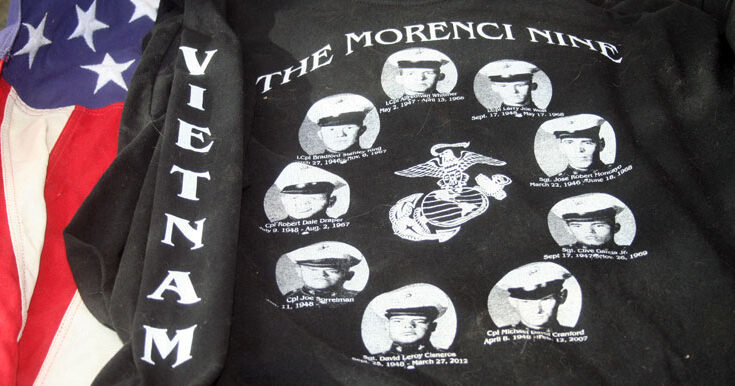

Cranford, known simply as “Mike,” was one of the legendary “Morenci 9.” They were nine kids who joined the U. S. Marines after graduation from Morenci High School in 1966. Only three made it home alive. Stories about the “Morenci 9” have appeared in national newspapers magazines and books.

A book about the group, “The Morenci Marines” by ASU History Professor Kyle Longley was published in 2017. It is a very in-depth look at their story. Do not look for the word hero or any cheap platitudes. The book really hits home.

Family members and friends who are at his funeral said Cranford would have felt disdain, if not outright contempt, at being called a hero. Those closest to him say he was what he was: A loving and admired husband, father, friend, cowboy, fisherman, and hunter. He did not tolerate fools.

Politicians and those who are clueless about military service are quick to use the word hero. By doing so, they degrade the meaning. Perhaps they also think John Wayne actually fought on Iwo Jima when in fact he never served a single minute in the military.

At an event in Clifton a few years before Cranford’s death, former Marine and Medal of Honor recipient Sgt. Robert O’Malley said he was not a hero, despite having been awarded the nation’s highest honor for bravery. O’Malley was the first Marine to receive the Medal of Honor for combat in Vietnam during Operation Starlight in 1965.

“I’m no hero,” O’Malley told a crowd at American Legion Post 28. “The only heroes are the guys who didn’t make it back.” Cranford later told a group later gathered outside the Legion he could not have agreed more with O’Malley.

Interestingly, O’Malley, who has been in the national spotlight, knew all about the Morenci 9. He said he felt honored to meet Cranford, Leroy Cisneros, and Joe Sorrelman, the other two Morenci 9 survivors.

(Cisneros died in 2017 in Yuma, where he resided.)

People such as Cranford, Sorrelman, Cisneros, and O’Malley represent how most Marines and other service veterans who returned from Vietnam and other wars feel about their service. They did what they felt they had to do. They take great pride in their service but never do they call themselves heroes.

For many, serving their country is a matter of paying their dues. They are only doing what others before them have done. One Vietnam vet said he sees himself as “an average American. I served my country, as did my forefathers, to be free.”

The news media has played a big role in cheapening the meaning of a hero. Hair-sprayed television news anchors gush the word with seeming glee. They jump at the opportunity to refer to anyone in uniform as a hero. Maybe that is because most reporters today have never served in the military. The TV anchors have taken the use of the word hero to an extreme. Anyone who does something that is even a little bit outstanding is labeled as a hero. It is enough to make a person’s skin crawl.

Men like Sorrelman, Cisneros, and Cranford never thought of themselves as gallant. Indeed, they always saw themselves as regular guys. They are people who did what they did at a certain time in their lives and then went on with living as normally as possible.

We must appreciate and honor the Mike Cranfords, Leroy Cisneros, and Joe Sorrelmans of the world who made it back from a living hell and went on with their lives, marrying, raising families, and continue contributing to society in their own way.

We honor them with sincerity and deep respect. They were Marines to whom we will be eternally grateful.

We are grateful to the six who did not make it back, the ones whom O’Malley termed “the real heroes.” They are Sgt. Jose Robert Moncayo, Sgt. Clive Garcia, Lance Corporal Bradford S. King (Stan), Lance Corporal Alfred Van Whitmer (Van), Lance Corporal Larry Joe West, and Corporal Robert D. Draper. They are somewhere in the great beyond.

Marine Corps pride is based on a unique experience and Marine camaraderie is something unto itself. It is only something a Marine can understand and appreciate

“Once a Marine, always a Marine,” as the saying goes. Wanting or needing to be known as a hero is not part of that proud legacy. Being a hero, as are the six who did not make it back, is most certainly a legacy of deep Marine Corps pride.

How can it not be? The Morenci 9 gave it their all.

Semper Fi, Joe. Semper Fi, Sgt. O’Malley. The same to every Marine who served in “The ‘Nam.”