Contributed Photo

By Jon Johnson

“Water, water, everywhere; Nor any drop to drink.” – The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

GRAHAM COUNTY – While Samuel Coleridge’s poem involves a sailor surrounded by saltwater he cannot drink, it could relate to issues in the Gila Valley, in which farmers may not be able to access their historically used wells while at the same time a pipeline capable of carrying enough water to serve 12,000 households on the San Carlos Reservation is not being used due to attorneys who claim to represent tribal interests.

To end the litigation and keep the water flowing to all parties, a coalition has formed under the name of the Upper Gila River Alliance.

Water is essential to life. The lifeblood of the Gila Valley comes from the water along the Gila River, which has been fought over by users up and down the Gila River for decades.

The Gila River Indian Community Water Rights Settlement was approved and implemented by the Water Settlements Act of 2004 and provided the Gila River Indian Community (GRIC) with a water budget of 653,500 acre-feet of water per year. An acre-foot of water the amount of water to cover one acre, one foot deep, and comes out to about 325,851 gallons. Water for the settlement is comprised of water from the Central Arizona Project, Gila River, Salt River, and groundwater.

The settlement also provided a resolution for enforcement issues surrounding the Gila Decree, Globe Equity No. 59, that had been the subject of litigation between GRIC, the United States, and non-Indian users in the Safford, Duncan, and Virden Valleys, according to the United States Department of Justice.

From the settlement, the Consumptive Use and Forbearance Agreement (CUFA) was produced and Gila Valley farmers retired 3,000 acres of previously decreed irrigated land and agreed to meter its wells and only use a total of 6-acre-feet per acre annually, whether taken from the river itself or from wells. However, while there for most of the negotiations, the San Carlos Apache Tribe did not sign the CUFA as other GRIC members did.

Since they didn’t sign, the tribe’s attorneys are now attempting to shut down those aforementioned wells on the basis that they are too close to the river and are “illegally” drawing river water from below ground that “belongs” to tribal interests.

Out of the CUFA, the Emery Pipeline was built to deliver drinking-quality water to the San Carlos Apache Reservation. The pipeline was developed with a stipend of $15 million that was earmarked for such a project by Sen. Jon Kyle in the CUFA. Water for the pipeline comes from Goodwin Wash, provided by wells purchased by the Gila Valley Irrigation District. Historically, the wells have produced fresh water in abundance and it is not tied to the Gila River.

The 36-inch and 30-inch pipeline can deliver around 10,000 gallons per minute of fresh water to the reservation at the touch of a button (and even a cell phone), yet attorneys for the San Carlos Apache Tribe (SCAT) have blocked construction of the pipeline at the tribal boundary and it sits there, plugged. When water is turned on to the pipeline – which has already cost $4 million to build to the reservation boundary – the only place it is currently pumped is into the Gila River.

Why would attorneys for SCAT not want the pipeline to service the tribe? According to the Upper Gila River Alliance, one reason is that attorneys are currently filing lawsuits against Gila Valley farmers asking the federal court to shut off their wells, claiming the water taken out of the wells infringes upon the tribe’s right to Gila River water. The wells in question have been used in the Gila Valley since the 1930s and ensure a consistent water supply for agriculture, according to the Alliance.

Alliance member Justin Layton farms roughly 1,300 acres of cotton in the Gila Valley. He said it is the attorneys and not the people they allegedly represent who are the problem and won’t even allow for an open dialogue.

“We don’t know that the regular members of the tribe are fully aware of what their opportunity is with this pipeline,” Layton said. “We’re not trying to point fingers at the reservation, and the alliance is not taking sides in any way. We strongly feel this is a win, win solution for both sides.”

What the Alliance wants is an open dialogue with the SCAT, its leaders, and the residents of the reservation. They want to stop both sides from having to pay attorneys for litigation and sit down and help each other out like neighbors.

“Our solution is let’s not fight about it and we’ll give you 10,000 gallons of water (pumped per minute), which is almost enough just by itself to satisfy all of their farming needs if they wanted to farm or if they wanted to take that water and do something else with it,” Layton said. “We’re open to any negotiations that they want to discuss.”

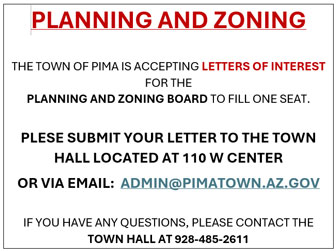

The Alliance has garnered support from local businesses, as well as the municipalities of Pima, Thatcher, and Safford, and the Graham County Chamber of Commerce. The Alliance asks that readers visit its website here and share the story.

Layton said it would cost roughly another $8 million to increase the pipeline across the reservation and finish it to where the tribe could utilize the water. He said the Gila Valley Irrigation is ready to do just that.

“We feel that if we could get all lawyers out – ours included – that we could sit down and talk,” Layton said. “That’s what we would love to do. We feel we have an equitable solution . . . I think we really can work together. Water is in short supply, especially here southeast Arizona along the Gila River. It’s not the best source of water, so if we work together it will be equitable for everybody.”

“We can either continue the path of costly litigation or move forward as friends and neighbors . . . recognizing water is the key to our shared future and prosperity. The choice is clear,” – Upper Gila River Alliance