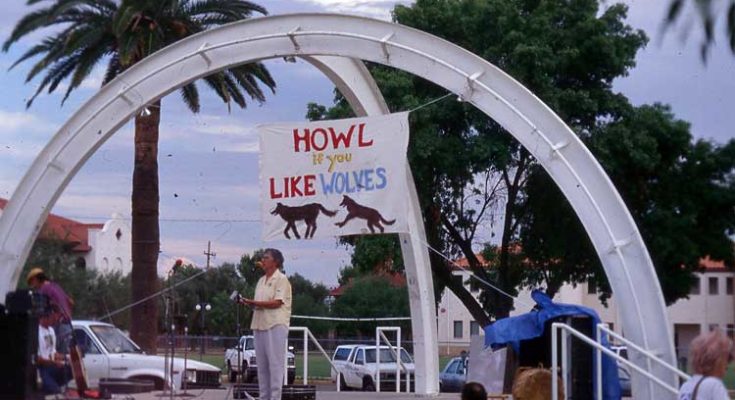

Photo By Dexter K. Oliver: Bobbie Holaday is shown here holding a Mexican gray wolf recovery fundraising rally in Tucson in 1994.

Editorial By Dexter K. Oliver

It just happened again. Another woman suddenly segued from her previous life experiences to become an immediate expert advocate for the Mexican gray wolf. This is just the latest in a lengthy pattern that is as easily tracked as the tell-tale clues left by a serial killer.

U.S. District Court Judge for Arizona, Jennifer G. Zipps, persuaded by environmental groups such as the Center for Biological Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife, and the Grand Canyon Wildlands Council, filed a ruling on April 2, confirming her qualifications in the field of reintroducing endangered carnivores. This, of course, is not something listed in her résumé. But she jumped into the deep end feet first anyway, declaring within a 44-page ruling, “to move forward with what the science says, and it says the Grand Canyon and that region is absolutely critical to be part of this recovery . . . ” Yep, critical to a subspecies that never lived there; that’s a unique argument.

I looked up her education at the University of Arizona and Georgetown University Law Center and found no indication that science courses were prevalent in her curriculum. Still, she went on in her recent ruling, “by failing to provide for the population’s genetic health it has actively imperiled the long-term viability of the species in the wild.” (She meant subspecies, I’m sure.)

Well, if you throw enough mud at a wall some of it is bound to stick, and she was right in that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), along with its sometimes-recalcitrant lackey the Arizona Game and Fish Department (AZGFD), has failed in a successful reintroduction of Mexican gray wolves. But that’s hardly a singular feat. They also failed in the reintroduction of thick-billed parrots, masked bobwhite quail, California condors, and black-footed ferrets despite whatever smoke and mirrors agency hype to the contrary is currently being fed to a gullible public.

The Mexican gray wolf reintroduction project just had its 20th anniversary earlier this year. As with ferrets and condors, such efforts and expenditures of multi-millions of dollars continue as open-air zoo experiments where people (paid with taxpayer dollars) daily interact with the animals to try and keep the leaky ark afloat. They feed these “wild” animals, they medicate them, they protect them by killing other real wildlife that poses threats, and they are taught and encouraged to lie about the realities of on-the-ground failures. If they have a complete lack of integrity they will retire off the backs of the often dead or dying charges of theirs.

This is not hearsay; I’ve seen all of this first hand as an agency employee dealing with the ferret, condor, and Mexican wolf reintroduction programs. The FWS and AZGFD are not fans of mine.

But back to the odd combination of women and Mexican gray wolves. There would arguably be no Mexican wolf reintroduction in the USA or Mexico if not for Tucsonan Bobbie Holaday, a city woman who had a wolf/dog hybrid for a pet and assumed wild wolves were just as cute. She kept pushing Terry B. Johnson, the slickest used car salesman the Arizona Game and Fish Department (AZGFD) ever employed, to have the diminutive wolves reintroduced. Johnson assured her that all it would take was money and a little public noise. So Holaday started P.A.W.S. (Preserve Arizona’s Wolves) and campaigned tirelessly getting the funds and signatures on petitions to influence the FWS who oversaw threatened and endangered species.

The first time I met Bobbie Holaday was at an official wolf reintroduction meeting at Hannigan Meadow south of Alpine in 1994. I was representing the local U.S. Forest Service (FS) wildlife division. When we were introduced she held her hand out and demanded money from me. I declined.

That night, she and the late Beth Woodin, an AZGFD commissioner and ardent wolf lover, went out howling in the forest. At the time this was part of a prerequisite action to make sure there weren’t already wild wolves still around before reintroduction could begin. The women had a lot of fun doing it. It is important to note that neither of these women nor the others like them, lived in wolf country. If they had I guarantee they would have been singing a different tune.

I later ran into Bobbie again at one of her many fundraising rallies in Tucson. It was easier for her to get money to bring back an apex predator to the landscape from people who would never be directly impacted by it. Interestingly enough, when Mexican gray wolves were finally released in 1998 into what was being called the Blue Range Recovery Area neither Holaday nor Johnson was invited to attend.

A woman by the name of Diane Boyd-Heger was hired by the FWS to run the on-ground recovery program. She was a breath of fresh air in what was already being seen as a flawed project. Boyd-Heger had extensive field experience dealing with wolves in the northwest. She knew they weren’t cuddly playthings like Bobbie Holaday’s wolf dog. She knew that the zoo-born wolves that had been transferred to specially constructed pens on the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) in New Mexico weren’t being properly prepped to survive on their own in the wild. And she knew how to talk to local ranchers and help assuage their well-founded fears about depredation. She quit less than a year into the program and left while her integrity was intact. Val Asher, a mule packer/trapper was another early employee on the wolf project who also bailed out quickly. I applaud both for their principles and honesty.

Fast forward to 2006 and I was working as a field biologist on the San Carlos Apache Reservation west of Safford. My job was to determine what predators were killing the tribe’s cattle in the wild northeast reaches of the reservation. These included mountain lions, black bears, coyotes, and Mexican gray wolves. Years before, I had been there trapping problem wolves with a federal Wildlife Services employee, so I knew what to expect.

For some insight into where the wolf reintroduction program was at that time, four Apaches and I were sent to the wolf pens at Sevilleta NWR and to meet with the “integrated wolf team” (personnel from both the FWS and AZGFD) in Alpine. Female employees and female volunteers were in the majority and my Apache companions (two men and two women) were aghast at how the wolves were treated religiously as “spiritual powers” by the Anglo women present.

It was disheartening to see these recovery team women were still feeding dry dog chow to the wolves as preparation for life in the wild. It reminded me of a former female partner of mine, Angie McIntire, with the AZGFD feeding canned cat food to captive born black-footed ferrets prior to their reintroduction into the wild. She hated watching them actually kill live prairie dogs that had been captured for that purpose. Twenty years later she’s still working for the state wildlife agency.

When the FWS was finally sued into releasing a new recovery plan for Mexican gray wolves at the tag end of 2017, I had to shake my head and laugh. The demands were now for three times as many wolves as initially proposed, 180 million additional taxpayer dollars, and 25-35 more years of trying to get things right. All of this would certainly provide enough job security for Sherry Barrett, the current Mexican wolf recovery coordinator, someone who gave up her claim to scientific morality long ago.

Changing the goal posts, adding more “cross-fostering” of zoo-born puppies with those in the forests, and ignoring proven science about population sizes and where these wolves had once lived all can now be seen as feminine interpretations of business as usual in these reintroduction attempts. No surprise that a female federal judge has joined the lineup of clowns in the on-going circus. Judge Zipps is claiming the Mexican gray wolves need to be in geographical areas they never inhabited in numbers several hundred more than ever existed. Andrea Santarsiere, a senior attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity in Tucson is egging her on, insisting the wolves be placed (and of course cared for by people) not only in the Grand Canyon but also the southern Rocky Mountains of New Mexico.

Where is the real science in any of this? It was thrown under the bus long ago and replaced by emotional claptrap. Arizona has had two successful reintroductions of wildlife. Railroad men brought in and released Yellowstone, Wyoming elk to replace the extirpated native Merriam’s elk and the late John Phelps (AZGFD) brought in Louisiana otters and dumped them in the Verde River and its tributaries. Neither required hands-on human help after the releases. See the difference?

These projects divert funds from other wildlife that need help before becoming endangered. We should have learned from these reintroduction failures that our attitude of omniscience is flawed. Certainly, they should be attempted but they should also have sunset clauses that close them down in a timely fashion if they are not working. Dragging them out so some biologists and environmentalists can have jobs is counter-productive. Expanding human populations, destruction of habitat and climate change will be hard challenges for all wildlife, not just the charismatic few.

Dexter K. Oliver is a freelance writer and wildlife consultant who has worked extensively with threatened and endangered species in the Southwest, Mexico, and Costa Rica.

The views and opinions expressed in this editorial are those of the author.