Photo Courtesy Dexter K. Oliver: Seven-year-old Dexter K. Oliver in a cage at the Bronx Zoo playing with carnivorous Komodo monitors (dragons).

Column By Dexter K. Oliver

I really wasn’t born in a barn but did grow up behind the scenes at one of the most notorious zoos in the United States (as well as a natural history museum and city aquarium). And I never knew the Mbuti pygmy called Ota Benga, he died 32 years before I was born, but we trod some of the same winding paths between the exhibition halls and wildlife enclosures at New York City’s Bronx Zoo. The facility was also called the New York Zoological Park and is now headquarters for the Wildlife Conservation Society.

It was missionary-turned-explorer, Samuel Verner, who got this story started. He travelled to the Congo area of Africa to bring back some diminutive natives to show off at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri. He purchased Ota Benga from some African slave traders for a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth. Born in 1883, the pygmy was an overnight star at the Fair, not so much for his amiable personality as for his stature and teeth that had been filed to sharp points.

Oddly enough, there is an Arizona connection to the tale. Geronimo, billed as “The Human Tiger”, was also being paraded around the same show as yet another oddity. It is reported thatGeronimo got to know and admire Ota Benga. The two together would certainly have been an impressive sight.

After the World’s Fair closed down, Samuel Verner somehow wrangled a room for the African to live in at the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Ota had free run of the five-story building complex, as did I six decades later when my father was director of that institution. But he preferred being outside and Verner convinced William T. Hornaday, the director of the Bronx Zoo at that time, to allow the man to live on the premises as an unpaid animal keeper.

Hornaday soon realized that the public was even more interested in Ota Benga than the wild animals on exhibit. In September of 1906, in the monkey house at the Bronx Zoo, Ota was put on display in a cage each afternoon as some sort of “missing link” between the great apes and white Homo sapiens. The rest of the time he was able to roam the 265 acres of the zoo and do as he wished. This was a direct precursor to my own time there half a century later.

African-American clergymen, unlike the New York Times newspaper which saw nothing wrong with the arrangement, raised a ruckus. Their complaint was that Ota Benga was being exploited as representing Darwin’s theory of evolution which directly refuted the principles of Christianity. Director Hornaday quickly grew tired of the fuss and turned Ota Benga over to a black minister, James H. Gordon, who took him under his wing. Gordon had the pygmy’s sharp teeth capped and dressed him in American style clothes. The preacher helped improve the African’s English, impressed the Bible on him, and helped him find paying work.

By 1916 Ota Benga was fed up with it all. He wanted to return home but couldn’t because of travel restrictions due to WW I. So Ota made a ceremonial fire, broke the caps off of his teeth, and shot himself with a borrowed pistol. He was 32 or 33 years old.

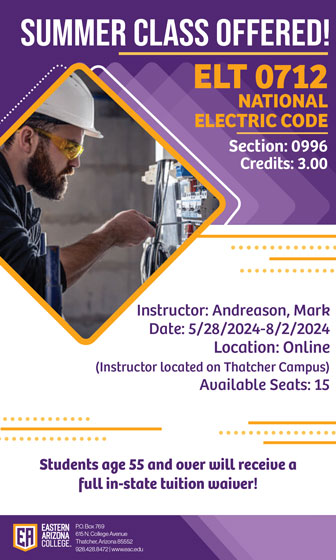

Fast forward fifty years and my father, Dr. James A. Oliver, was curator of reptiles and amphibians at the Bronx Zoo. He had recently received two new additions to the reptile house, full-grown Komodo monitors (also called Komodo dragons). At seven years old, I had already been allowed to explore all of the zoo’s grounds and had played with baby alligators, Galapagos tortoises, and other assorted wildlife. Wanting some publicity shots of the new acquisitions, my father set up a photo op with me in the enclosure housing some of the world’s largest lizards.

Komodo monitors are carnivorous and take down and devour full grown deer and wild pigs, as well as introduced water buffalo. They manage this by biting their prey with large, curved, serrated teeth and the aid of venom from complex glands in their lower jaws. The two specimens at the Bronx Zoo had been fed a few whole, unplucked, dead chickens so they wouldn’t be hungry when I was allowed into the cage with them. My father stood off to one side in case something went awry. My mother always claimed that the subsequent photos made her blood run cold but I quite enjoyed myself. As perhaps Ota Benga occasionally had when he too was in a pen looking out to where the public was restricted. People watching can be entertaining.

Almost seven decades later, I once again found myself on one side of a cage-like barrier while the citizenry were on the other side looking in, just like at the Bronx Zoo

The Country Chic Art Gallery & Crafts Boutique (which houses the Duncan Visitors’ Center) was putting on one of its second-Saturday of the month street parties with vendors set upall around. My wife, Glenda, and I had been tapped to provide the live music (or at least some amplified noise) to attract passersby. Since it was still hot, we found a secluded position under some shade trees behind a chain link fence that bordered the sidewalk. Watching the people on the far side of the barrier peering in at us like we were some sort of exotic animals made my mind flash back to Ota Benga and Bronx Zoo days. Strange how words or events trigger mind associations with things already experienced.

We’ll be back there next month, peddling my DVD/CD (see The Gila Herald editorial “Outlaw Americana Music”, Jan. 5, 2023) and surreptitiously even a few copies of my now black market book (see The Gila Herald editorial “Banned in Duncan”) but only to those with the correct password. Which currently is the answer to the question: About how old is the planet earth we’re standing on? Hint: It is not six thousand years. That book has been referred to as just another forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil. But I couldn’t comment on that.

Dexter K. Oliver is a freelance writer and observer of the human condition from Duncan, AZ.