It happened in the midst of bloody, muddy war

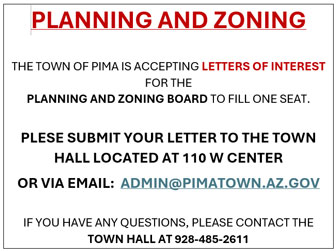

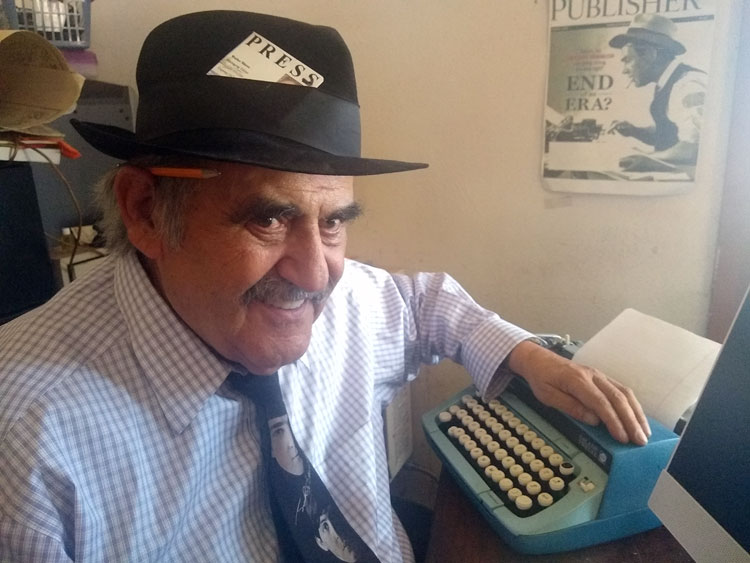

Column By Walt Mares

It happened more than a century ago. It is regarded as one of the most storied and strongest moments in history. On Christmas Eve 1914, in the dank, muddy trenches on the Western Front of World War I, a remarkable thing happened.

It came to be called the Christmas Truce. And it remains one of the most storied and strangest moments of the Great War — or of any war in history.

Here we are, more than a century later, and much can be taken and learned from that event. What we can learn and hopefully practice does not involve countries at war. It involves what is happening in America, our own beloved country, today.

There are no sounds of thundering cannon fire. It involves what is happening in our hearts and minds. In the streets and what happened at the voter polls. It centers around the malignancy currently affecting our society; hatred, anger, mistrust, an absence or lack of compassion, and unwillingness to find a common ground. It is not that we cannot find common ground. It is a matter of unwillingness and failure to do so.

At the root of the malignancy is a tumor created mostly by politics and the deep division it has created in America.

We enjoy the greatest freedom of any country in the world but many fail to acknowledge or appreciate all that we do have. Instead, there is a misappropriation of what the term freedom means.

A great lesson can be taken from the Christmas Truce of “The war to end all wars” as it was called after the shooting and killing were over. Why can we not call a truce of sorts here in America during the 2020 Christmas season? Why should it be so difficult for a week or two, or even one day, to set aside our anger and hatred and know and feel some peace and calm?

The essence of Christmas is the birth of a very special child whose purpose was to bring peace and love to the world. Should that not be foremost in the minds, hearts, and actions of those who claim to be Christians? There is a great absence of that. Instead, anger and hate too often rule the day.

Please, let us call for and observe a truce in our beloved America.

The Truce

The following is from a story by A.J. Baime and Volker Janssen on the History Channel online network

British machine gunner Bruce Bairnsfather, later a prominent cartoonist, wrote about it in his memoirs. Like most of his fellow infantrymen of the 1st Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, he was spending the holiday eve shivering in the muck, trying to keep warm. He had spent a good part of the past few months fighting the Germans. And now, in a part of Belgium called Bois de Ploegsteert, he was crouched in a trench that stretched just three feet deep by three feet wide, his days and nights marked by an endless cycle of sleeplessness and fear, stale biscuits and cigarettes too wet to light.

“Here I was, in this horrible clay cavity,” Bairnsfather wrote, “…miles and miles from home. Cold, wet through and covered with mud.” There didn’t “seem the slightest chance of leaving—except in an ambulance.”

Then the singing started

At about 10 p.m., Bairnsfather noticed a noise. “I listened,” he recalled. “Away across the field, among the dark shadows beyond, I could hear the murmur of voices.” He turned to a fellow soldier in his trench and said, “Do you hear the Boches (Germans) kicking up that racket over there?”

“Yes,” came the reply. “They’ve been at it some time!”

The Germans were singing carols, as it was Christmas Eve. In the darkness, some of the British soldiers began to sing back. “Suddenly,” Bairnsfather recalled, “we heard a confused shouting from the other side. We all stopped to listen. The shout came again.” The voice was from an enemy soldier, speaking in English with a strong German accent. He was saying, “Come over here.”

One of the British sergeants answered: “You come half-way. I come half-way.”

Fraternization ensued

What happened next would, in the years to come, stun the world and make history. Enemy soldiers began to climb nervously out of their trenches and to meet in the barbed-wire-filled “No Man’s Land” that separated the armies. Normally, the British and Germans communicated across No Man’s Land with streaking bullets, with only occasional gentlemanly allowances to collect the dead unmolested. But now, there were handshakes and words of kindness. The soldiers traded songs, tobacco, and wine, joining in a spontaneous holiday party in the cold night.

Bairnsfather could not believe his eyes. “Here they were — the actual, practical soldiers of the German army. There was not an atom of hate on either side.”

And it wasn’t confined to that one battlefield. Starting on Christmas Eve, small pockets of French, German, Belgian, and British troops held impromptu cease-fires across the Western Front, with reports of some on the Eastern Front as well. Some accounts suggest a few of these unofficial truces remained in effect for days.

For those who participated, it was surely a welcome break from the hell they had been enduring. When the war had begun just six months earlier, most soldiers figured it would be over quickly and they’d be home with their families in time for the holidays. Not only would the war drag on for four more years, but it would prove to be the bloodiest conflict ever up to that time. The Industrial Revolution had made it possible to mass-produce new and devastating tools for killing — among them fleets of airplanes and guns that could fire hundreds of rounds per minute. And bad news on both sides had left soldiers with plummeting morale. There was the devastating Russian defeat at Tannenberg in August 1914 and the German losses in the Battle of the Marne a week later.

By the time winter approached in 1914, and the chill set in, the Western Front stretched hundreds of miles. Countless soldiers were living in misery in the trenches on the fronts, while tens of thousands had already died.

Then Christmas came.

First-hand accounts recalled bottles, smokes and barbering

Descriptions of the Christmas Truce appear in numerous diaries and letters of the time. One British soldier, a rifleman named J. Reading, wrote a letter home to his wife describing his holiday experience in 1914: “My company happened to be in the firing line on Christmas eve, and it was my turn…to go into a ruined house and remain there until 6:30 on Christmas morning. During the early part of the morning the Germans started singing and shouting, all in good English. They shouted out: ‘Are you the Rifle Brigade; have you a spare bottle; if so we will come halfway and you come the other half.’”

“Later on in the day they came towards us,” Reading described. “And our chaps went out to meet them…I shook hands with some of them, and they gave us cigarettes and cigars. We did not fire that day, and everything was so quiet it seemed like a dream.”

Another British soldier, named John Ferguson, recalled it this way: “Here we were laughing and chatting to men whom only a few hours before we were trying to kill!”

Other diaries and letters describe German soldiers using candles to light Christmas trees around their trenches. One German infantryman described how a British soldier set up a makeshift barbershop, charging Germans a few cigarettes each for a haircut. Other accounts describe vivid scenes of men helping enemy soldiers collect their dead, of which there was plenty.

Soldiers playing soccer in No-Man’s Land during the Christmas Truce in 1914.

An impromptu ‘kickabout’

One British fighter named Ernie Williams later described in an interview his recollection of some makeshift soccer play on what turned out to be an icy pitch: “The ball appeared from somewhere, I don’t know where… They made up some goals and one fellow went in goal and then it was just a general kickabout. I should think there were about a couple of hundred taking part.”

German Lieutenant Kurt Zehmisch of the 134 Saxons Infantry, a schoolteacher who spoke both English and German, also described a pick-up soccer game in his diary, which was discovered in an attic near Leipzig in 1999, written in an archaic German form of shorthand. “Eventually the English brought a soccer ball from their trenches, and pretty soon a lively game ensued,” he wrote. “How marvelously wonderful, yet how strange it was. The English officers felt the same way about it. Thus Christmas, the celebration of Love, managed to bring mortal enemies together as friends for a time.”

Gradually, news of the Christmas Truce made it into the press. “Christmas has come and gone — certainly the most extraordinary celebration of it any of us will ever experience,” one soldier wrote in a letter that appeared in The Irish Times on January 15, 1915. He described a “large crowd of officers and men, English and German, grouped around the [dead] bodies, which had been gathered together and laid out in rows.” The Germans, this British soldier said, “were quite affable.”

Just how many soldiers participated in these informal holiday gatherings has been debated; there is no way to know for sure since the ceasefires were small-scale, haphazard, and entirely unauthorized. A Time magazine story on the 100 anniversary claimed that as many as 100,000 people took part.

Today

We are supposed to be an advanced society from the way the world was 106 years ago in 1914. With what we see happening today makes one wonder just how far we really have come. No way was America and the world as divided as what we are seeing and experiencing today. May the Christmas season shed light on what and where we are and what we can become.

Peace to all. God bless America and the world. Let us begin healing.