By Emily Fox-Million/Cronkite News

PHOENIX- Turquoise light wraps around the painted portrait of a dead girl. It is part of a makeshift memorial that sits off a highway road beneath Mount Triplet in Peridot. After a year, it has begun to moulder, the teddy bears hanging from a chain-link fence, their fur stiff from sun and dust. The once-bright flowers have faded and become brittle at the edges.

Emily Pike’s mural faces the desert and has started to fade. The elements thin the fabric, drain the color, and fray the edges. Here, a year since the girl’s remains were found on Valentine’s Day, 2025, off U.S. 60 near Globe, time shows itself in what has begun to fade — and in what hasn’t.

Emily Pike’s name hasn’t faded. She is a law. She is a movement. She is a reminder. Her name is spoken in classrooms, at vigils, in group homes, and at the Arizona Capitol.

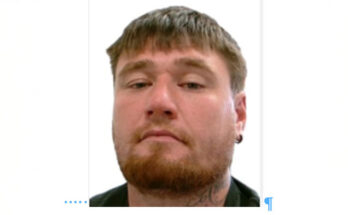

Pike was just 14 years old when she went missing from a group home in Mesa. Valentine’s Day marked one year since her remains were found in trash bags. There have been no arrests in the case.

Her uncle, Allred Pike Jr., remembers her as a teenager who wanted to go to college. Who loved art. Who cared for her siblings and her parents.

“She endured a lot in her young life, but yet she looked towards the future,” he said.

He hopes people remember her as her family does.

“Smart, intelligent,” he said. “And even though she’s gone, she made a positive, positive impact on this world.”

He said that impact is tangible.

Since her disappearance, lawmakers passed Emily’s Law, establishing the Turquoise Alert system to expand public notification when Indigenous people and other vulnerable individuals go missing. Before her case, there were no statewide alerts exclusively for missing Indigenous people in Arizona.

“The first major one is the Turquoise Alert,” Pike Jr. said. “Not perfect, but it’s a step in the right direction. Saving lives. Law enforcement paying more attention. Bringing awareness.”

For Mary Kim Titla, executive director of United National Indian Tribal Youth, legislation alone does not define Emily’s legacy. Titla said she sees her death as a catalyst.

“We didn’t have this before the Emily Pike case, and now we have it,” Titla said. “So that’s a plus.”

She says the law may be in place, but real change will depend on continued oversight, accountability, and a commitment from communities and lawmakers to ensure no other child falls through the cracks.

“What happened to Emily Pike is never far from our minds,” Titla said. “It reminds us that we must promote a message of not only safety, but also of justice.”

Emily’s story has also intensified conversations around Missing and Murdered Indigenous People, a crisis that families have raised concerns about for decades, but that often struggles for public attention.

Emily’s name traveled across tribal communities and beyond state lines.

“It’s not just about Emily,” Pike Jr. said.

There are other people on other reservations who are still missing, and Pike’s story has forced broader recognition that Indigenous families are still waiting for answers, he said.

“Making sure that her murderers are caught because we need to let all Indian Country know that their lives matter,” he said. “They’re not forgotten.”

Her legacy lives in conversations about what happens before girls go missing.

Pike lived in a group home when she went missing. Her case prompted scrutiny of group home oversight, placement practices, and cultural disconnection for Native youths in care.

Pike’s family filed a lawsuit against Sacred Journey Inc., operator of the group home in Mesa. In it, the family alleges that Sacred Journey Inc. failed to provide adequate care and was negligent in its hiring. Sacred Journey Inc. responded in a legal filing saying that the parents were neglectful, and that Pike left the group home “of her own free will.”

Elisia Manuel, founder of Three Precious Miracles, works weekly inside group homes across Arizona, leading cultural workshops for residents and staff. She describes culture as not just ceremonial – it gives young people a sense of identity, routine, and belonging that can help ground them in otherwise uncertain living situations.

“These kids are craving their culture, and it’s not being provided,” Manuel said.

In talking circles, she has watched teenagers bead jewelry and begin to cry because it reminded them of their grandmother. She has heard youth say the smell of sage feels like home.

“If you imagine stripping your kids away from not only everything that they’ve known … but also their culture, their people, their food — that is hard,” she said.

Pike’s case, Manuel said, pushed the system to acknowledge that safety includes making sure Native children are placed in homes where their culture, language, and identity are supported.

She advocates for more Native foster parents, stronger kinship placements, and more intensive cultural competency training for those working inside group homes.

“When a child goes into foster care, we always say it takes a village,” she said. “But we have to actually build that village.”

Titla agrees and said that her work with Native youths focuses on leadership and wellness, but added that safety education and accountability must remain central.

“Anyone who works with a young person must be trained,” she said. “They have to know how to build rapport. They have to know how to prevent violent things from happening to young people.”

Pike’s name, Titla said, should continue to challenge institutions long after headlines fade. She worries there is a danger in turning a child into a symbol so large that the person disappears.

Her uncle wants people to remember who she was — a young girl who deserved stability, education, and the chance to grow up.

“If Emily were still here today,” he said, she would have deserved “a stable home, environment, education … just giving her the opportunity to be a kid, enjoy life, no worries.”

Her uncle hasn’t returned to the stretch of roadside where her body was found in months.

The desert is already erasing what’s left. The candles have burned out. The toys sit untouched. Sun and dust continue to wear down the memorial. But one thing has not changed.

Pike is dead, her case remains unsolved, and her uncle – and the rest of her family – still wait for justice.

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.