AZGFD study quantifies effect of Arizona’s unchecked burro populations

Contributed Article/Courtesy AGFD

PHOENIX — A recent study by biologists at the Arizona Game and Fish Department (AZGFD) found that non-native, feral burros are harming some keystone plant species in Arizona’s Sonoran Desert landscape. These changes in habitat are already harming some species of wildlife and may pose a challenge to more species in the future.

“For a number of years in areas with burros, our biologists anecdotally observed trees that were over-browsed and that had ripped bark and branches,” said Clay Crowder, AZGFD assistant director, Wildlife Management Division. “We initiated this study to have concrete data and a better understanding of the impact that the burros have on wildlife and their habitats.”

For the study, biologists chose the areas in and around Lake Havasu and Lake Pleasant. These locations were ideal because they included both areas with herds of burros and nearby areas with similar vegetation types, but without burros present.

Biologists established transects at multiple sampling sites, where they measured vegetation metrics, including size, density, and foliage density, as well as age structure for certain species. They also recorded evidence of wildlife such as tracks and dung piles. They looked for signs of deer and bighorn sheep and collected data on small mammals, reptiles, and birds.

“Our most significant findings were related to the vegetation,” said Esther Rubin, AZGFD Research Branch chief. “In one of the primary vegetation types, the ground cover was 30% lower in burro areas. Plant and foliage density were also lower, and some of the plant species were smaller, but some of the most concerning findings had to do with palo verde trees, ironwood trees, and saguaro cacti.”

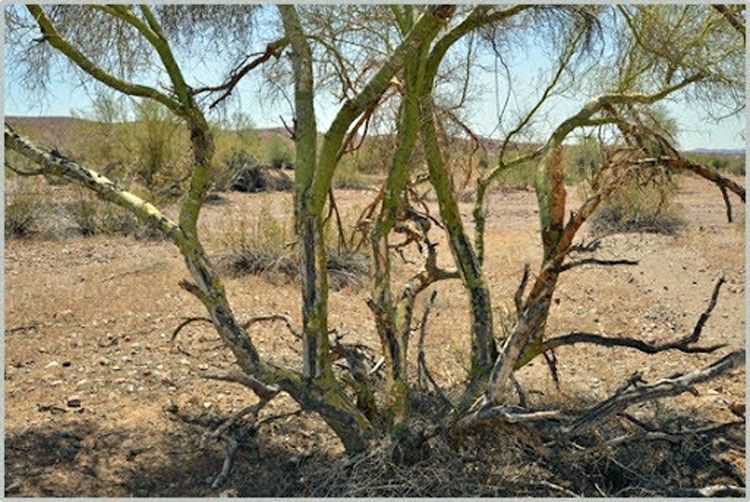

Both palo verde and ironwood trees are typical of the Sonoran Desert and can live for upwards of 100 years and beyond. In their natural state, these trees grow very full and bush-like, with overhanging branches often touching the ground and creating a refuge of shade and protection for wildlife and for other plants. For this reason, palo verde and ironwood trees have been referred to as “nurse plants” because they protect young plants of multiple species. In areas with burro presence, that protective habitat is being destroyed.

“When you see these trees in the landscape, everything from burro height down is completely eaten,” Rubin said. “And when you get closer, you can see teeth marks where the burros chewed and ripped the bark away, which can eventually kill the tree.”

When these trees are damaged and no longer provide a shady refuge, many plant and wildlife species are negatively affected; however, one Sonoran Desert native is being hit particularly hard in active burro areas: the iconic saguaro cactus. Taking about a decade to grow just a few inches, saguaros depend on trees like the palo verde to be their “nurse plants,” providing the protection they need to make it to adulthood. In areas with burro presence, the study found a 63% lower ratio of young to adult saguaros.

“Saguaros are considered a keystone species, providing cover or forage for over 100 species of animals,” Rubin said. “Reduced recruitment of saguaros could have negative effects on the habitat and wildlife for decades, possibly centuries.”

Unlike native ungulates living in the Sonoran Desert – think bighorn sheep and mule deer – burros possess several physiological traits that cause them to use and impact vegetation differently.

“Burros and other equids have a less efficient digestive system than bighorn sheep and deer. So burros need to consume more plant material than an animal of equal size,” Rubin said. “Burros also have upper incisors that allow them to grab and tear vegetation in a way that native wildlife cannot.”

Despite the negative effect burros have on wildlife habitat, AZGFD does not manage these animals. Burros are protected under the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 and are managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and, in some cases, the U.S. Forest Service. The BLM established seven herd management areas (HMAs) in Arizona, and each HMA was evaluated to determine how many burros that landscape could support while maintaining what the Federal government refers to as a “thriving natural ecological balance”. This number is known as the appropriate management level (AML).

“If you add all of the HMAs in Arizona together, the BLM has determined that the collective appropriate number is about 1,400 burros,” Rubin said. “The BLM estimate for the state is about 10,000 burros, and this doesn’t include the many burros that have spread to non-HMA areas. The actual number is likely much higher.”

Burro numbers are far above recommended levels — and growing, at a rate of about 20% a year. Burros have also spread beyond designated HMAs, leaving many uncounted and unmanaged. Add to that their ability to thrive in the desert even when vegetation is poor, and it’s easy to see how Arizona ended up with a burro overpopulation.

The BLM is responsible for monitoring burro numbers and, when necessary, removing burros from the landscape to holding areas. They also have an adoption program for burros, and there is research being done on fertility control. However, none of these are options that will quickly return burro numbers to their appropriate management levels.

“The long-term effect of burros on habitat remains a concern,” Crowder said. “The BLM has the legal requirement to manage burros at numbers that maintain a thriving natural ecological balance, and our findings indicate that this requirement is not being met.”

The interplay between management difficulties and the public’s fondness for the burro is the topic of an upcoming documentary by Zala Films, titled Burrocracy.

“When it comes to the burro issue, no one is looking through the same lens,” said Burrocracy filmmaker Asali Echols. “Our hope is to take a step back from the disagreement and arguing, look at the topic from a broader sense, hear the different perspectives, and maybe there could be some new ideas about how to move forward.”

For now, Rubin hopes that this study will give AZGFD’s federal partners a better understanding of the effects that feral burros are having on the Sonoran Desert’s habitats and wildlife.

“We manage the wildlife, and we need healthy habitat to support them,” Rubin said. “There are about 300 species that rely on the Sonoran Desert as their home, and I feel like the foundation of this home is crumbling — burros are nibbling it away.”