Column By Dexter K. Oliver

There must be some kind of way out of here. Said the Joker to the thief. There’s too much confusion. I can’t get no relief.

All Along the Watchtower – Bob Dylan

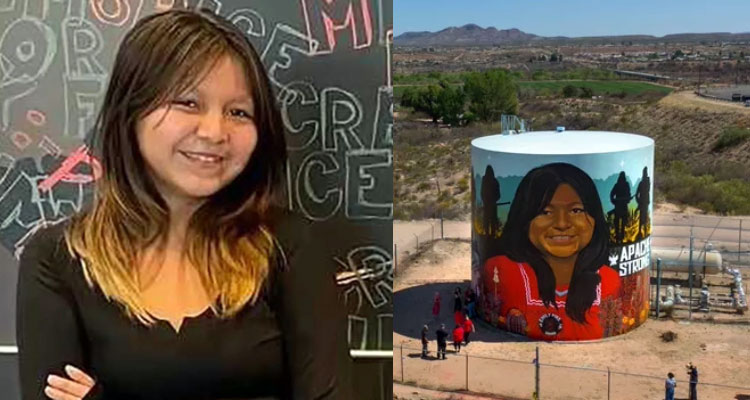

I watched the celebration of life services for 14-year-old Apache Emily Carla Pike on the evening news with sadness, frustration, and unanswered questions. Not just about who the perpetrator or perpetrators of such a heinous crime might be, but of all the history that had led up to the murder and dismemberment. Having butchered my fair share of big game animals, I know precisely what such disarticulation entails and beseech law enforcement agencies to get a conviction as soon as possible.

I was struck by one of the speakers at the service stating that the inhabitants of the San Carlos Apache Reservation would “Continue to write her story; laws and lives will be changed.” One can only hope this comes true because it is not just the annals of the slain girl but of her people and their culture that led to this moment.

Another spokesperson mentioned that Emily Pike was “In a better place, out there praising God.” With a background of drum beats and chants, I couldn’t help but recall my six months living and working as a wildlife field biologist at Point of Pines on the reservation and the paradox of existence there. I wondered exactly what spiritual entity the speaker had been invoking, the traditional Apache creator, Usen (or Ussen), or the Christian god that was forced upon a defeated people by the European victors. It was a legitimate question because religion caused an overwhelming amount of confusion and strife to those who came later. And still does.

Just as Charles Dickens’ 400+ page masterpiece, “A Tale of Two Cities,” explores universal human themes, both historical and current, any fully realized narrative about Emily Pike should do the same. It would start with the arrival of an Athabascan-speaking group from Alaska some 700 years ago into the Southwest. They would be called Apachu (enemy/outlaw) by the already-established pueblo Zunis. The Spanish conquistadores who showed up not much later would change this to the current derivation, Apache. Like indigenous human populations worldwide, they would self-identify simply as Ndeh (spellings differ), The People. Their nomadic lives were immersed in hunting, foraging, and, most importantly, raiding to survive. They referred to Mexicans, whites, and non-Apaches as Ndah (spellings differ).

A truly tangled can of worms awaits any anthropologically inclined writer of the Emily Pike account from this point onward. It would include the corruption of the conquerors and the perhaps well-intentioned but destructive history of Indian schools far removed from the reservation that sought to assimilate Apache youth into a culture completely unlike their own. The attempted disavowing of their religious beliefs, language, and even clothing was brought about through isolation, starvation, and beatings. All of which eventually found its way back to their allotted home where it festered and was passed down as mental, physical, and spiritual abuse through generations.

The unresolved, and perhaps unresolvable, clash of a Native American religion that included White Painted Lady, Child of Waters, Killer of Enemies, and the Ga’an (spellings differ), or mountain spirits, competing with a Christian Father, Son, and Holy Ghost continues. I learned early on that the subjugator’s faith community might be all right for social gatherings, but the Apaches weren’t about to give up their traditional ways completely. Carrying a medicine pouch with sacred cattail pollen and items with spiritual and protective powers is still as prevalent as ceremonial drumming. The competing superstitions of both persuasions have proven bewildering, divisive, and paralyzing. One embraces a heaven with pearly gates and golden streets, while the other visualizes a happy hunting ground with no Mexicans or whites.

This brings up more queries for any author wanting to chronicle Emily Pike’s all-too-brief life: Did she have a traditional Sunrise (puberty) Ceremony (the $10,000+ cost of which is prohibitive to many Apache families and should be subsidized for all who want one with money from their casinos)? Did she know the ways of Shash, the bear who was her brother, uncle, or grandfather? Why was she in a group home far from the reservation that provided “out-of-home care and a safe, nurturing environment”? In a matriarchal society, was that not available within her extended family, including the customary surrogate parental protection of her “aunties”? Why was this child described by many in the tribe as sweet, kind-hearted, funny, and beautiful sent away? These are questions within questions that deserve answers. One would imagine that guilt, finger pointing, and soul searching have the reservation in enough turmoil right now that laws and lives will indeed be changed. But the ultimate responsibility perhaps lies within an overpoweringly bigoted white culture that passed along many of its worst trends.

I was hired by the San Carlos Apache Recreation and Wildlife Division in 2006 to run a field study of what big predators were responsible for killing their cattle. I was the only white person on the crew and had been chosen for my outdoorsmanship, long history of working with wildlife, and ability to pass a drug test. I had been fingerprinted before when dealing with endangered species for federal agencies, but the tox screen was new. I did not fear Big Foot or The Little People who ran naked through the reservation forests hunting elk with spears. I could handle ancient pottery shards without calling up ghosts from the past and didn’t turn back when a coyote crossed my path or an owl flew across the road in daylight. The coyote tradition was Navajo, as was my boss, who had married an Apache woman in San Carlos.

I lived at Point of Pines, a remote outpost in the eastern, forested section of the reservation. My partner was a 22-year-old Chiricahua Apache woman who stayed there occasionally but whose real ambition was to be a blackjack dealer at the Apache Gold Casino in San Carlos. It was she and her family who mostly educated me in the ways of their people. I had worked on the Tohono O’odham and Navajo Reservations before and could adapt quickly. The endemic problems with alcohol, drugs, and violence were nothing new to me. Nor were the disappearances of both young males and females from their homeland (MMIP = Missing or Murdered Indigenous People). Or the trials, tribulations, and triumphs of the Twin-feather (Two-spirit) folks, the native gay community.

When I finally resigned six months later it wasn’t because of a bear trying to kill and eat me in my assigned house trailer (which gave me my Apache name, Ndah shash bedán, the white guy who is bear food) or being an Apache tourist attraction or on the receiving end of racism (“You are not one of us” and “I hate white men” are both direct quotes). It was the combination of tribal hierarchy corruption that influenced my job; the Point of Pines Cattleman’s Association allowing its herd to die off from dehydration, starvation, and exposure, as well as the unavoidable contending with “Indian time.” Unlike the Mexican version of mañana, mañana, putting things off until tomorrow, Indian time meant when designated, or later, or not at all, and there was no way to tell in advance which it would be. My detailed resignation letter was rejected outright by the head of the wildlife division, stating it would get him fired. I left anyway.

I wrote a novel, “The Raven’s Beak,” that showcased much of what happened on the San Carlos Reservation while I was there (available at the Duncan Visitor’s Center or DKO, PO Box 716, Duncan, AZ, $20). It also includes an incident on the White Mountain (Fort Apache) lands just to the north. A young native woman, caught up in ancestral ways, was killed, stabbed 58 times, for being a witch. It reminded me of the hundreds of years of auto de fé, the burning at the stake that Catholics employed to rid themselves of infidels.

My New Mexico writer friend, Lif Strand, recently published a novel, “Stolen Sisters,” (available on Amazon, $21.99) that shines more light on the dilemma of Missing or Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW). Anyone genuinely interested in telling the whole story of Emily Carla Pike could find both books enlightening. I, for one, will look forward to somebody else writing “the rest of the story,” to quote the late, long-running radio host Paul Harvey. It would rank up there with Truman Capote’s most famous work, ‘In Cold Blood.’”

Dexter K. Oliver is a freelance writer, wildlife field biologist, and observer of the human condition from Duncan, AZ. His latest book is “#13 A Baker’s Dozen: An Eclectic Anthology”